Or, What’s a Paradigm Worth These Days?

I.

Recently I’ve found myself completely blocked on a writing assignment.(1.) It’s for a fellowship application; the host institution brings together historians and social scientists under the rubric of understanding and influencing government policy, so it’s a bit of a chimera in terms of disciplinary focus.

The assignment in question calls for:

a proposal for a New York Times opinion piece which applies a major finding from your research to a current public policy problem. … it must describe a full op-ed that you might write, and explain its relevance to current events.

Some words pop out there, no? “Relevance,” “current events,” “a major finding from your research”… you can see how those might bring a historian to a standstill.

It’s not that I don’t want my research to be relevant or au courant. Quite the opposite. Here’s the problem, though: drawing big lessons, lessons big enough to cross time and space, is pretty much the antithesis of dissertation work, and, I think, historical thinking more generally.

Dissertations are about the super-specific. Historians are too, in a way: we’re in the business of explaining the unique, the contingent, the transformative event (or series of events). When context is king, the work is, by definition, not portable.

When I’ve heard historians explain the practical aspects of their research, it usually hinges on perspective. The past is a foreign country, they say, they do things differently there — and we can learn from that. History teaches us about the oddly contingent and jury-rigged origins of things in our own world — what I think of “naming the monster,” the fantasy/horror/folklore trope that knowing the name of a devil gives you the power to exorcise it, a technique being used to very good effect in the history of sexuality and gender at the moment (think of the difference between “marriage the eternal traditional bulwark of human society,” and “marriage the socially constructed category that is always changing” in a courtroom, and I think you’ll see what I mean). Likewise, the foreignness of the past, especially the past of one’s own culture, is an object lesson in how diverse human institutions, motives, and actions are (or rather, were).

In a practical sense, then, historians usually explain their work as the building blocks for something new — by reminding us of what possibilities once existed (a form of naming the monster) — or, more commonly, as a caution against hubris and self-satisfaction. Both are exercises in perspective; knowing where you came from, and what other choices there are out there.

These are good lessons, I think. But it doesn’t get you very far to figuring out what early American ideas about the China trade can say about public policy today.

II.

The always-interesting Tim Burke has been ruminating on a related topic lately. Thinking on the practical bases for popular anti-intellectualism, he’s frustrated with the answers his fellow humanists have come up to explain the value of their knowledge. What’s important about knowing about Hawthorne, or the Constitutional Convention, anyway?

That this is a question at all is, in part, due to the success of the humanist project over the last half-century or so, and the collapse of what Burke terms “ramrod” forms cultural authority — not a bad thing, on balance (“good riddance,” Burke says). But the problem of how to explain the value of this kind of knowledge remains: “educators haven’t arrived at a substitute rationale that’s both persuasive and pervasive.”

Burke argues that this value can be demonstrated in a couple of different ways. One is through sheer enthusiasm for the subject — but passion is hard to instill through training, and even more difficult to generalize. Another answer comes out of the literacy (aka “critical thinking skills”) that humanist work teaches. Burke describes this explanation as a focus on “practicality.”

This is a new iteration of the very old idea that humanist knowledge enriches the storehouse of the mind; Burke’s spin is novel in that it is focused on the problems of a information-rich age, where the ability to “read” in different media and environments, and make judgements about that content — which is now far more important than accumulating content itself (that’s easy).

Any way you put it, though, the ends are the same: a richer, more well-lived life:

Cultural and historical literacy enriches your rhetorical and interpersonal skills. It helps you imagine other people, which is the key to so very much in life: to love well, to raise children well, to live in community well, to self-develop, to choose when and how to fight for yourself and your beliefs.

III.

Burke’s solution to the problem of finding ways to make humanist knowledge relevant is, I think, just a more broadly stated version of the historian’s go-to answer for the value of historical work. But instead of using specific content to demonstrate perspective, it’s the literacy and rhetorical skills developed through repeated efforts of that sort that provide the value.

Perhaps not precisely relevant to my problem of figuring out how my research is relevant to the theoretical readers of my op-ed piece. But thinking in terms of pervasive, persuasive, and practical is a good start. You can decide for yourselves how well my actual proposal meets that standard tomorrow.

To be continued…

1.) A shocking revelation from a blogger who has quarter-long gaps between posts, I know.

2.)Tim Burke,”Hester Prynne, Schmester Prynne, or Sarah Palin’s Ressentiment Clubhouse,”Easily Distracted, 19 January 2010.

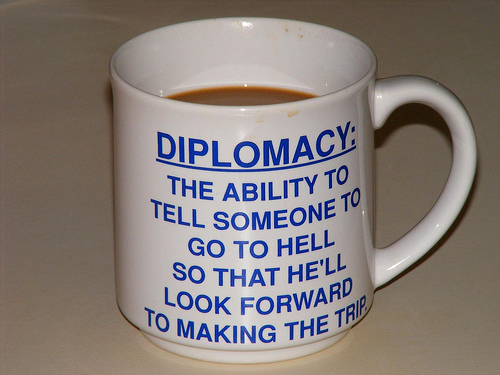

Image cite: Gabriela Camerotti, “Practical Magic,” Flickr, CC License