Or, How U.S. Steel Now Resembles the Royal African Company – and What That Means for American Democracy & American Capitalism

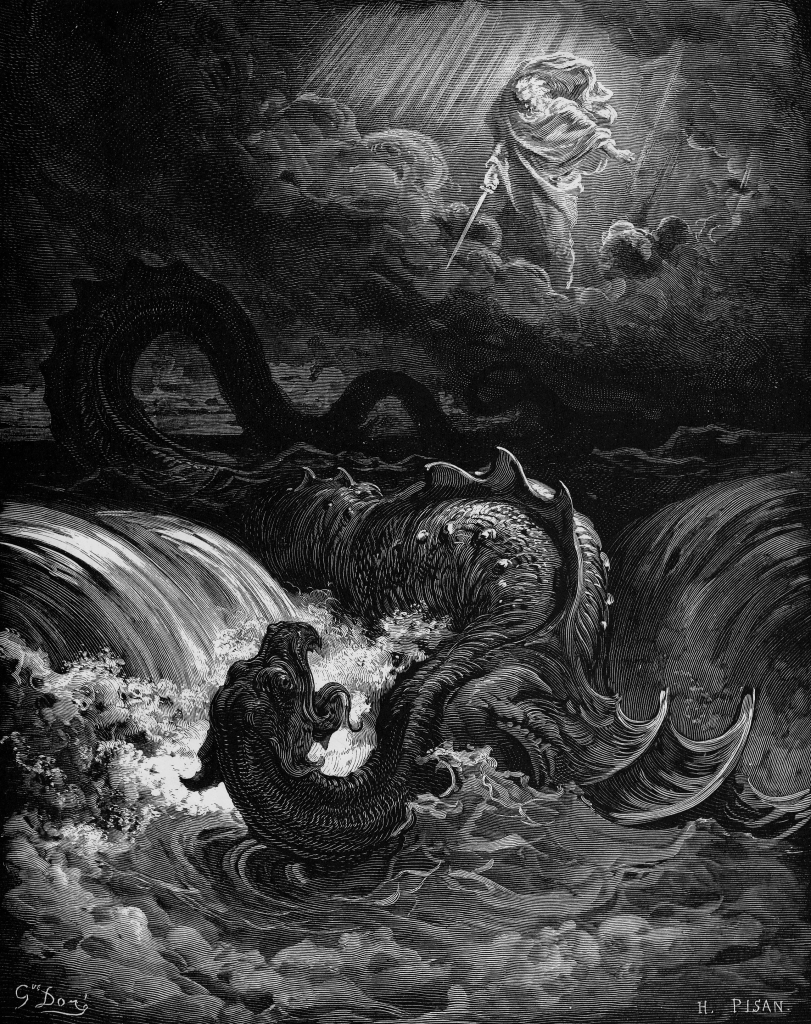

How does an autocrat affect the business world? As Leviathan thrashes his bulk and churns the seas, how many adventurers’ ships do his waves swamp and founder? And how might the folks interested in those ships attempt to appease Leviathan?

The US is six months into the MAGA Restoration, and having effed around, I think we’re starting to find out.

~~*~~

On June 18, 2025, Nippon Steel acquired U.S. Steel for $14.1 billion dollars, making the long-lived American industrial corporation into a wholly-owned subsidiary of the Japanese company. The deal to create the world’s second-largest steel operation was a long-simmering one, running over eighteen months, largely due to federal opposition on “national security” grounds, first from the Biden administration and then the Trump regime.

The impasse broke in mid-June, when the companies involved found a novel way to satisfy Trump’s vanity: they promised him a powerful, personal “golden share.” Journalists at the NYT, Bloomberg, WSJ and elsewhere all reported – seemingly only on the basis of company-issued materials – that holding this “Class G share” would grant President Midas-Touch unusual power over the operations of the new subsidiary, still to be named U.S. Steel.

“Nippon Steel and U.S.Steel struck a National Security Agreement with the US, in which US Steel will issue a so-called golden share to the government. The golden share gives consent rights to the US president concerning reductions in capital investments, changing US Steel’s name and headquarters, redomiciling outside the US, transferring jobs or production outside the US, acquisitions and decisions to close or idle existing facilities.”

Some context: a “golden share” is a special class of stock that allows its holder, typically a government, to outvote all other shareholders in some circumstances, like during proposed charter amendments. The term appears to date to Thatcher-era Great Britain, though the practice of a government assuring itself control of an important corporation by taking an ownership stake is far older (central banks, for example, often operate this way). In the contemporary moment, “golden shares” seem to function like a glitzed-up, nationalized version of the dual class shares that oligarchs, like Mark Zuckerberg and Warren Buffett, use to maintain personal control of their companies without tying up their capital in equity.

But while “golden share” structures are common outside the US – Brazil holds a “golden share” in aircraft manufacturer Embraer, the PRC owns shares of companies like ByteDance, etc – the arrangement is quite rare, and perhaps unique, in the US. Even when the federal government re-capitalizes failing companies, as it does during bailouts (e.g. GM’s after 2008, or any number of railroads, airlines, and financial institutions), US officials have stayed far away from using the resulting equity to assert control over operations, much less business strategy.

And indeed, the US Government still does not own a “golden share” of U.S. Steel. As corporate law professor Brian JM Quinn noted on Bluesky, the amended certificate of incorporation for the post-merger U.S. Steel – the corporation’s charter document – does not create any “G-Class” shares, nor does it grant the US Government stock of any kind. The business press’s breathless reporting was inaccurate – or rather, reflected the statements of corporate and regime officials, but not the legal documentation. [1]

Instead, Article VI U.S. Steel’s new charter grants “Donald J. Trump” vast control over the operations of the company. While he is serving as president, “written consent of Donald J. Trump or President Trump’s Designee” is required for the corporation to: alter its charter, change the company name, move its headquarters out of Pittsburgh, re-domicile outside the US, change its capital investments, sell any production location, acquire any other company, implement price changes, accept financial assistance from the Japanese government, reduce employee salaries, or “make material changes to the Corporation’s existing raw materials and steel sourcing strategy in the United States.”[2]

When or if Donald J. Trump is no longer president – a future the new charter does not contemplate except by implication – these powers fall to the US Department of Treasury and the US Department of Commerce, though who within those departments can act, or how they are to act together, is unspecified.

So: Nippon Steel has provided a specific person, President of the United States Donald J. Trump, with governing power over their subsidiary corporation, a company worth (as of last week) $14 billion dollars. He holds this power not as an owner of equity, or as a director with fiduciary duties to equity owners, but simply by virtue of his office and political power.

To be blunt: is the kind of thing corporations do to satisfy autocrats. Only in a personalist dictatorship do you give the head of state a role in your foundational corporate charter; it’s a courtier’s pact, made to curry special favor, and bind a political patron to the business.

What’s curious, here, is not that corporations are seeking Trump’s favor – his constant demands for bribes are by now a regular feature of American governance, part of the wider MAGA Restoration’s effort to manage government as a protection racket. Nor is it surprising, these days, that the President of the United States has arranged matters such that his office provides him with ill-gotten cash flows through ownership of corporate ownership or licensing of corporate assets; that, too, is standard federal procedure now.

No, what’s odd about this U.S. Steel deal is that the Trump regime appears to have arranged personalized governing power over a corporation, without acquiring ownership. They seized the opportunity to assert sovereign authority over a national enterprise, through a single person, not an owner’s property rights. In U.S. Steel, they have recreated the powers of a king.

~~*~~

There are many ways to think about the shape that business takes in an autocracy. We don’t lack for models: from the Congo Free State under Leopold II to Jim Crow Mississippi to fascist Italy or today’s PRC, there are diverse examples of how capitalist expansion continues – and, arguably, thrives – under despotic rule of many different types and in many different places.

But this U.S. Steel disaster resonates with a deeper history, I think, the place and period of where capitalism first emerged, alongside – and in partnership – with ambitious autocrats: early modern England. At least, there seem to be several familiar chords in this music. First, in this period, the British (neé English) empire relied on corporations as a critical tool for colonial and commercial expansion – corporations that, for the most part, were created by the Crown, not Parliament. Second, the early British empire was quite unstable, riven by repeated cycles of revolution and restoration, coups and counter-coups – which provided lots of opportunities for negotiating and re-negotiating the relationship between state and corporations, monarchs and market institutions, and a lot of explicit writing and wrangling about what these relationships could, should, or did mean.

Finally, the autocrats of the period – and in particular, the well-coiffed but fragile-necked Stuart kings – provided the whetstone against which early Americans, and their political heirs, sharpened their ideas about liberty to a cutting edge. It’s a period rich in relevant material, as well as direct influence, on the politics of our present moment.

Which brings me to the Royal African Company. The RAC was a joint stock trading corporation with a monopoly on all English trade with West Africa. First granted letters patent (e.g. a charter) by Charles II in 1660 under the title “Company of Royal Adventurers into Africa,” it took on its more well-known name, and some additional powers, with a re-chartering in 1672. [3]

The RAC was, in many respects, a bog standard corporation of its time and place. It was one of dozens of companies chartered in 17th-century England, and like the Levant Company, the East India Company, or the Hudson’s Bay Company, its charter not only granted its associates unified legal personhood – and thus the ability to concentrate and deploy capital beyond the means of any one merchant – but also monopoly rights over a specific trading territory, and governing power there. Like these other companies, the RAC was explicitly a tool for colonization and imperial competition: it could establish forts, manors, and plantations, set up courts, and develop, marshal, and maintain military force on land and sea, as needed to fulfill that purpose.

While it’s fashionable in corporate law and finance circles today to approach corporations as organizations with ultimately “private” origins that the state must, reluctantly, regulate to maintain the basic health, safety, and financial transparency standards markets need to function, the RAC reminds us that this libertarian conception of corporate life is detached both from historical reality as well as the letter of the law. Like modern corporations domiciled in Delaware, the Royal African Company was a subdivision of the state, a temporary division of sovereign authority, granted to a body of subjects to accomplish a purpose – and therefore ultimately and always a creature of government, in all senses. [4]

Two things made the RAC unique, amid this host of incorporated adventuring companies. First, while the company’s initial business was the gold trade, it quickly – and quite successfully – expanded into slave trading. Indeed, a few years into its existence, the RAC became the dominant player in the trans-Atlantic traffic in human beings, and over its life it shipped more people across the Atlantic into chattel bondage than any other single institution. [5]

Second, from its first charter onward, the company’s lead founder and “first governor” (e.g. board chairman and CEO) was the king’s brother, James, Duke of York. And James… James was a special guy. Amid some serious competition from his grandfather, father, and elder brother, James Stuart, Duke of York and (briefly) King James II (of England and Ireland) and VII (of Scotland) distinguished himself for his zeal for building an absolute monarchy based on the divine right of kings – and, unsurprisingly, also by his penchant for cruelty and the brutal persecution of his critics.

While James II didn’t meet the sharp end his father did – he fled England before anyone could effect the traditional familial separation between head and body – his time as Duke and then King made a lasting impression on British political development, as an example of what not to do. Following his fall, the power of British kings was forever broken, more tightly circumscribed by law and kept in check by the active exercise of sovereign power by Parliament.

Why? Well, all the Stuarts had been committed a project of centralizing power under the Crown, and growing the monarchy’s bureaucracy at the expense of other governing institutions. Briefly checked by the loss of Charles I’s head and the interregnum, the post-Restoration Stuarts doubled down on the monarch’s right to arbitrary authority. So under Charles II, the monarchy took to simply disappearing troublesome subjects to foreign prisons “beyond the seas” – a practice Parliament attempted to circumscribe by legislating habeas corpus in 1679. And because James II was the last – and arguably the most aggressive – champion of this project, he receives particular opprobrium for it. As historian Holly Brewer has recently reminded us, James II expanded on his family’s efforts, efficiently corrupting the judiciary with patronage in order to remove any check on the monarch’s whims. (A tune that should sound familiar to modern Americans…)

But back to the RAC: James’s executive role in the company was not in name only. He used the company to advance his colonial projects all over the Atlantic world, as a means to supply the slaves that his colonial adventures in North America and the Caribbean needed to profit. And he also wielded state power on its behalf – directing the Royal Navy to seize African forts during wars against the Dutch, for example. (Among other wartime accidents, these Anglo-Dutch conflicts led to James, as the Duke of York, briefly becoming the proprietor of the tiny, failing sub-colony of Delaware – a disappointment to all involved, surely).

In practice and in theory, there was no clear line between the operations of the RAC as a capitalist enterprise, and James’s personal exercise of autocratic power. Indeed, they co-constituted each other – with humanity all the worse for it.

~~*~~

But what does the Royal African Company have to do with U.S. Steel? I would argue there is a similarity in political shape. The grant of governing power to a ruler is not an act undertaken in a political economy defined by free enterprise and universal rights; it’s not even the kind of play one makes in a robust oligarchy. Rather, it’s the move a board of directors makes when playing court politics, in a monarchy.

Too, the fact the Trump and his minions worked to produce this outcome – and not a simple bribe – makes it worse than bare graft. It’s an enactment of the MAGA Restoration’s theory of politics, of a piece with the anti-democratic philosophy the movement’s intellectuals advocate, the same philosophy that’s leading the regime to crush universities, the press, and tighten its chokehold on the federal courts and Congress. It’s a politics of absolute monarchy akin to what the Stuarts and their lackeys celebrated as divinely justified (an apologia constantly offered by Trump supporters, too). That autocracy has now come to corporate America.

But despite it’s best attempts, tyranny is never the only game in town. The House of Stuart was nearly a century fled from Britain’s empire, and their pretense to rule equally dead, when the American Revolution took its first percussive bloody breaths on Lexington Green. And yet, the Stuarts’ shade remained, substantial enough to cast a defining shadow when American patriots submitted a “history of repeated injuries and usurpations” to a “candid world” to demonstrate the “absolute Tyranny” of King George III. As they sought to justify themselves for rising to rebellion and declaring independence by reference to the King’s outrageous acts (like “transporting usbeyond Seasto be triedfor pretended offences”) American revolutionaries recalled and remade a political language first articulated by by a group of seventeenth century anti-Stuart partisans, the “Country Whigs,” within a broader European discourse about the necessarily popular roots of political order and legitimacy (e.g. “republicanism”). Stuart tyranny was the lens through which revolting colonials observed the actions of King George and Parliament, and it served as the foil to the English liberty they sought to restore through rebellion.

Americans identified the dangers of arbitrary monarchical rule in part through its corporate manifestations. The Tea Act, the legislation granting the East India Company a monopoly on tea sales in North America and laying a small tax on tea to pay for government bureaucracy, was condemned by Massachusetts Whigs as a “master-piece of policy for accomplishing the purpose of enslaving us.”[6]

That sounds like a wild overreaction to tax policy – and a weird reason to destroy millions in fragrant property – until you understand that like other British colonials, Massachusetts activists saw political events through the lens of Stuart abuses. A corporate monopoly, designed to generate taxes to fund state action, wasn’t just a discrete policy, but a conspiracy to undermine the imperial constitution and drown free men’s liberties. How did they know? Their political forefathers had lived through it one before, and written a great deal about it – and those essays survived and circulated widely among the politically engaged colonial elite; and too, the colonies they inhabited took the shape and form they did in no small part due to the actions – and reactions – to James II’s wielding of corporate power.

Based on their understanding of the Stuart example, they thought the leviathan’s bulk was necessarily nourished by blood flowing through corporate veins.

Thus, the legacy of the Royal African Company, and the importance of its corrupt echo in the corporate structure of U.S. Steel lies not only in the personal despotism these companies actively embodied or embody. It rests also in the liberatory ideology that tyranny inspired, as an instrument that detects corruption in the body politic as the rot sets in, identifies it as a danger to free people, and provides the means – the words and the actions – through which it can be opposed, and destroyed.

The best way to survive a cancer is to catch it early, and treat it. U.S. Steel’s new charter shows up as a large malignant mass on America’s scan; will we be willing to cut the tumor out before its too late?

————

[1] This is not the only way the business press’s breathless reporting was inaccurate. Several news reports have mentioned that Trump will also have the privilege of appointing a member of the board of directors. This claim appears to be based on social media posts from the US Secretary of Commerce, Howard Lutnick. But like the “golden share” itself, this provision this is not included in the merger agreement, the revised certificate of incorporation, or the revised corporate bylaws – though a more recent filing, from June 25, 2025, states that a new “Class G Director” will be appointed per the terms in the National Security Agreement, a document that has not been made public, and may never see daylight.

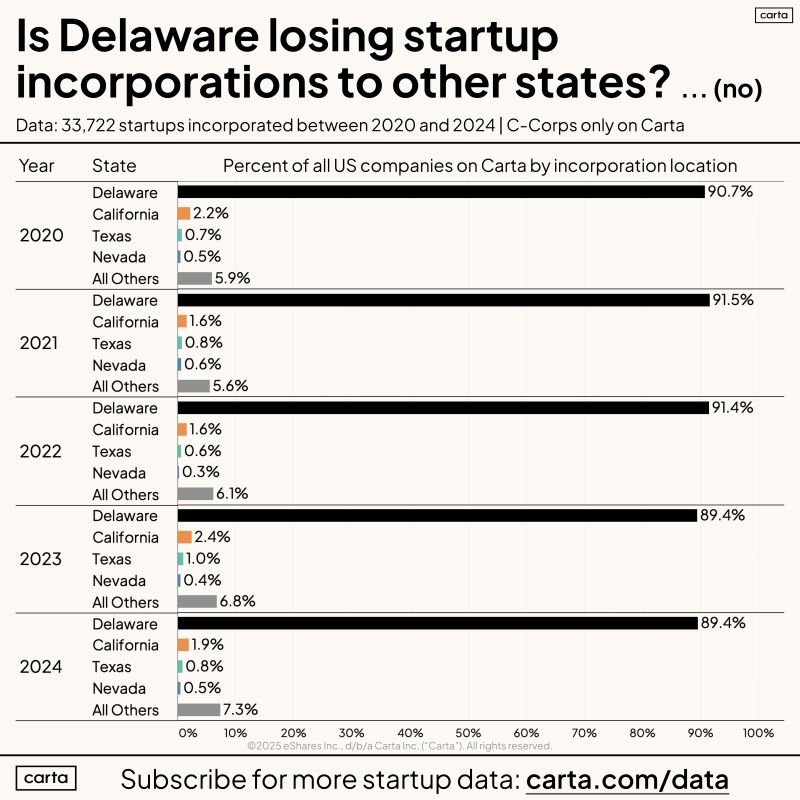

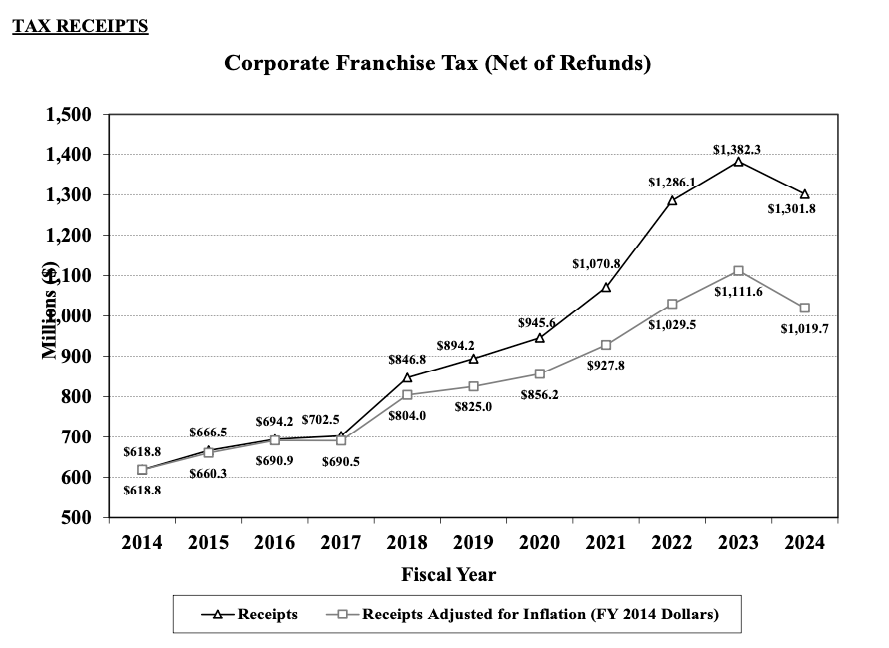

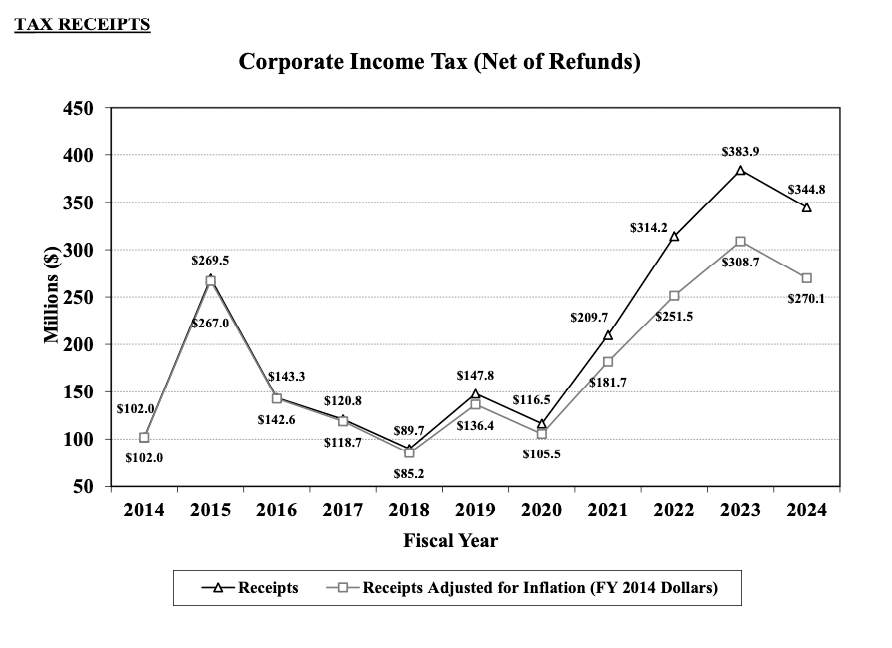

[2] Of course U.S. Steel was and remains a Delaware registered corporation. In some regards, one could read the new subsidiary’s corrupt charter as the logical fulfillment of the new permissive “private ordering” regime that that billionaire oligarchs, Delaware corporate defense attorneys, and their lackeys in the state legislature have been working overtime to retrofit into the Delaware General Corporate Law. What is a grant of power to a monarch, if not an exercise in removing shareholders’ influence on the corporation they own a putative stake in?

[3] For the 1660, 1662, and 1672 charters of these corporate entities that became the Royal African Company, see Cecil T. Carr, Select Charters of Trading Companies, A.D. 1530-1707, Publications of the Selden Society (London: B. Quaritch, 1913), pp. 172, 177, and 186 et seq.

[4] The source of “sovereign” authority was disputed, however. In theory, in the US today “the People” constitute “the state,” which creates corporations (state and federal). In seventeenth century England, however, the Crown asserted that authority, through the sovereign body of the monarch – though, at various moments Parliament also claimed that authority too, leading to some rather nasty civil conflicts, coups, counter-coups, and counter-counter coups, that were only resolved once the Dutch got involved – a messy outcome.

[5] The RAC shipped some 150,000 people during its primary years of activity, from 1672 to the 1720s. William A. Pettigrew, Freedom’s Debt: The Royal African Company and the Politics of the Atlantic Slave Trade, 1672-1752 (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2013), p.11.

However, British slave trading would soar to all-time world-historical highs only after the RAC’s monopoly was broken. Independent British slave traders then far surpasses – in a shorter amount of time – the human trafficking of every other slave-trading Atlantic nation. The end of the RAC’s monopoly was a development that planters in North America welcomed, by the way, as now they had cheaper sources for slaves. Another example of the magic of the free market, a blood-soaked sort of necromancy.

[6] In Consequence of a Conference with the Committees of Correspondence in the Vicinity of Boston . . . (Boston, 1773). See also: Benjamin L. Carp, Defiance of the Patriots: The Boston Tea Party and the Making of America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), 20, 246n33.

![Louis Dalrymple, “Uncle Sam’s Dismal Swamp,” Puck, November 15, 1893, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/ppmsca.29155. Print shows Uncle Sam sitting on a log in a swamp labeled "Spoils System" from which snakes labeled "Quayism", "Bardsleyism", and "Tannerism", and noxious fumes rise in the form of shades labeled "Raumism - Pension Swindler, Crokerism, McLaughlinism, Tweedism, Prendergast - Political Assassin, [and] Guiteau - Political Assassin". Also shown among the tree roots is Charles A. Dana.](https://daelnorwood.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/dismalswampcrop.png?w=839)