Or, What’s a Little Light Voting Restriction Between Friends, Across Decades?

Corporate Voters Project – Research Note #3

Having surveyed the swampy landscape of corporate voting in present-day Delaware, I’ve now turned to digging post holes in it. That is, to get a clearer sense of when as well as why the practice of enfranchising business entities took hold, I’m taking a closer look at a handful of municipalities with corporate citizens, by investigating the legal history of their charters – specifically, when corporate voting entered their basic law – and trying to contextualize those developments using historical newspapers.

First up? Dagsboro, Delaware.

~*~

Ten miles from the coast as crows and google maps fly, Dagsboro was first incorporated in 1899. The town proper was carved out of Dagsborough Hundred, in Sussex County. (“Hundreds” are unincorporated subdivisions of counties – not unique to Delaware, but unusually long-lived here, where they served as the primary local political unit from the colonial era through to the 1940s. Most were defined by waterways: “White Clay Creek Hundred,” in what is today Newark, centered on said creek, for example; there’s a similar story behind the much more metal “Murderkill Hundred”) [1].

According to Thomas Scharf, the excitable, voluble, and occasionally reliable nineteenth-century chronicler of Delaware history, Dagsborough Hundred was named after its lead proprietor under late British rule, John Dagworthy. Alternately described by Scharf in the course of one printed page as a captain, colonel, and general, in 1774, Dagworthy was granted generous tracts of land – known as “Dagworthy’s Conquest” – as a reward for military service rendered, and well-placed connections worked, in the Seven Years’ War. He repaid this boon during the American Revolution by seizing British war matériel and arresting accused loyalists. When not offering such forceful signs of ingratitude to the British Crown, Scharf records that “General” Dagworthy:

“built a capacious one story house upon an eminence at the east end of the town…The approach was a broad avenue lined with trees. There surrounded by his family and a retinue of slaves he dispensed a liberal hospitality.”[2]

What a swell a petty tyrant, eh?

When he died, Dagworthy was buried under the chancel at Prince George’s Chapel, a tiny but persistent house of worship, just off the main drag of what became the Town of Dagsboro in 1899.

Dagsboro’s inaugural charter has a number of interesting features – but corporate voting is not one of them. The municipal franchise, per Section 3, is reserved for tax-paying property owners: “every male taxable of said town above the age of twenty-one years” as well as the “husbands of woman freeholders in said town.” (It pays to marry well!)

The franchise was premised on landholding – a “freeholder” is a resident who owns real estate in fee simple – and, critically, paying in to the town treasury: to vote you had to be up-to-date on your assessed taxes.[3]

The amount of tax you paid mattered, too. You’ve heard of voting with your dollars? Well, so had the legislators who chartered Dagsboro. In their wisdom, they decided that this jumped-up village was going to be an oligarchy, not a democracy. At town elections “each person entitled to vote shall be entitled to one vote for each dollar, or fractional part thereof, which shall have been paid by them or their wives as town tax on the property so assessed.”

To put it more plainly: the more land you owned, and the more tax you paid, the more votes you could cast! Like most oligarchies, this regime lasted only a short while: in 1903, the charter was amended to eliminate the vote-per-dollar scheme – though voting was still restricted to landowners, or men who married women who owned land.[4]

The press noted the Dagsboro charter’s passage through the legislature in January 1899 only perfunctorily. There are more stories about the sick wife of the charter bill sponsor (and first town commissioner), Rep. William P. Short, and his subsequent arrest for bribery (later dismissed), than there are about Dagsboro’s creation itself.

That’s understandable: a town with at best one crossroads warrants little notice most days, and much less in a year when Delaware politics were as lively and consequential as they ever get. Dagsboro’s competition for column inches was, first, the extensive extralegal efforts of one J. Edward Addicks, erstwhile Republican, to bribe himself into the U.S. Senate (Rep. Short was part of that effort – caught but not prosecuted); and then second, the total revolution in the state’s political economy, via the wholesale adoption of the New Jersey corporate code. (This was Delaware’s bid to steal their northern neighbor’s revenue scheme – though it took until 1913 for fruit of that poisonous tree to fully ripen).[5]

~*~

Corporate voting first appeared in Dagsboro with the town’s re-chartering and re-incorporation in 1941. So far, I have only found spare notices of this in state or local newspapers: Sen. Alden P. Short shepherded the bill through the General Assembly, but what his relation was to William P. Short, or why 1941 was the year to do this civic business, remains unclear.[6]

What is clear, though, is that the 1941 charter enfranchises corporations to vote in bond referenda. In these “special elections,” residents and property owners, “whether individual, partnership or corporation” all received “one vote for every dollar and fractional part of tax paid.” Oligarchy, again!

Voting for annual municipal elections in Dagsboro was, in this revision, more open – reserved for taxpayers 21 and over, with no stated racial or gender restrictions – but the process became malignly unusual. To indicate their choice for town commissioner, voters “shall cross out the names of all candidates which he or she does not desire to vote for” – that is, in Dagsboro you vote via negation. I read this as a form of Jim Crow-restrictions in action: a purposefully confusing process put in place to allow white election officials to reject votes at their discretion. [7]

And while thus far, I have not found any newspaper accounts that shed light on why this re-incorporation happened when it did, I think it’s notable that the bond referenda section re-used the 1899 charter’s “one dollar, one vote” mechanism – even while other voting restrictions were loosened, or altered.

The past is never truly past, especially if property is involved.

~*~

In 1991, the Town of Dagsboro re-incorporated again, and once again revised its charter. This time corporate voting was brought fully into all elections, both annual and special. The path, again, for corporate enfranchisement was property ownership – though now limited to one vote per person/entity.[8] As with the 1941 revisions, the motivation for this overhaul is not immediately clear from the newspaper record – but there is a notable coincidence, involving sewers.

The charter revision bill was sponsored by Sen. Richard S. Cordrey, a powerful pol from nearby Millsboro, who was then serving as Senate pro-tem. And while Cordrey’s other initiatives made the newspapers regularly – there was a redistricting that session, as well as smaller fights with the Governor over appointments and the budget – Dagsboro’s new charter only appears in the press as a one-line entries in legislative recap articles.[9]

What did make the papers was a slow-moving effort by Sussex County to build new sewers to accommodate an ongoing wave of new residents and housing developments. Beginning in 1990, the County and affected towns – including Dagsboro – were involved in a series of lawsuits and legislative wrangling to select sites for wastewater treatment and disposal. By 1991 work was sufficiently underway on the job of replacing Dagsboro’s private septic systems with a County-administered municipal flush that the Wilmington News Journal, the state’s biggest newspaper, thought it warranted a town profile.

The New Journal’s Southern Delaware correspondent noted the Dagsboro was a sleepy place, with one hill, one stoplight, and one predatory, “hawk-eyed lawman” eager to “fatten the town’s coffers” with tickets written to out-of-towners. But beyond that picaresque character, the story was that Dagsboro’s citizens – and possibly it’s corporate voters, too – expected the sewers to set off a “boom time,” attracting new residents and new economic vibrancy into the town.[10]

My hunch is that sewers and corporate voting are linked, both metaphorically and politically. The 1991 charter revision, by empowering non-resident property owners, both human and corporate, could have been part of a horse trade, to get the infrastructure investment needed to enable a “boom time.” Giving corporations the vote could have been what was needed to get them to invest in the project of the town’s growth – and in return, corporations got to help decide how much they’ll pay for all the new shit they bring.

Call it the “Cum Cloacarum et Corporationes, Civitas” theory of government.[11]

~*~

For the curious and civic-minded, the Town of Dagsboro website explains local election procedures. If you are a human resident – but not lucky enough to be a property owner – you face some hurdles. You have to present yourself with identification and documentation at the Town Hall office, during business hours, to be certified and entered into the town voter registration book. (Unlike other Delaware municipalities, Dagsboro does not participate in the state voter registration system). Then, come election time, provided the clerk can find and verify you in that book, you can vote.

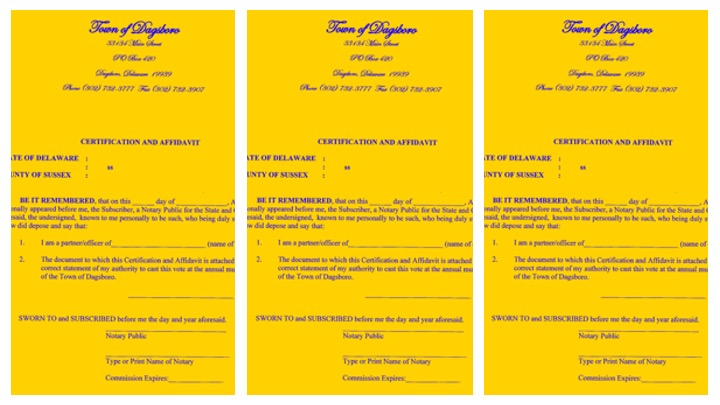

However, if you are a property owner – whether a natural person or artificial entity – your task is requires less of a time expenditure. Simply appear at the polling place with your name on a deed to a property within the corporate limits; and if “you” are a business entity – a partnership, or a corporation – you proxy must appear with that deed, plus “a certified resolution of said entity authorizing the person therein to vote for the entity.” Two pieces of paper, and you’re golden, no fuss, no waiting.

The Town of Dagsboro helpfully provides a standard certification form; all a corporation needs to do is fill in the blanks.

——–

[1] The best and most detailed account of Delaware’s extraordinarily creaky administrative state that I have encountered is Penjerdel Corporation and Pennsylvania Economy League, Historical Development of Local Government in the Penjerdel Region, Penjerdel Governmental Studies 1 (Philadelphia, PA: Penjerdel, 1961), https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/005888599.

[2] J. Thomas Scharf, History of Delaware, 1609-1888, 2 vols, (Philadelphia: L. J. Richards & co., 1888), 2:1335, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001874039.

[3] 21 Del. Laws, c. 285: “An Act to Incorporate the Town of Dagsboro,” Approved February 9, 1899, pp. 549.

[4] 22 Del. Laws, c. 437: “An Act to Amend Chapter 285, Volume 21, Laws of Delaware, Being Entitled ‘An Act to Incorporate the Town of Dagsboro, Approved February 9, 1899’,” Approved March 31, 1903, p.435.

Special thanks is due to Willard Hall Porter, Attorney at Law, who annotated his personal copy of the Laws of Delaware in bright red pencil to note this charter update. His copy was scanned in and made available by Princeton University via Hathi Trust. It takes a (long-dead) village to write a history, y’all!

[5] Typical of press coverage of the charter is “Legislature,” News Journal, Mon, May 5, 1941, p.4. On Short’s wife’s pneumonia, “Mr. Short’s Sad Message,” Wilmington Daily Republican, February 24, 1899, p.2. On his dismissed bribery indictment: “Kent Bribery Cases,” Middletown Transcript, April 29, 1899, p.3, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84026820/1899-04-29/ed-1/seq-3/

[6] 43 Del. Laws, c. 161: “An Act to Reincorporate the Town of Dagsboro,” Approved May 14, 1941; “Legislature,” News Journal, Mon, May 5, 1941, p.4.

[7] On bond elections, 43 Del. Laws, c. 161, Sec. 22(B)6; on regular muncipal elections, Sec. 5(D).

[8] 68 Del. Laws, c. 138; “An Act to Reincorporate the Town of Dagsboro,” Approved July 9, 1991. On annexations, see Sec. 3(F); on muncipal elections Sec. 7(G); and on bond referenda, Sec 33(A)5

[9] “Legislature,” News Journal, Thu, June 20, 1991, p.19; “Legislature,” News Journal, Thu, June 27, 1991, p.15; “Legislature,” News Journal, Sat, June 29, 1991, p.7; Nancy Kesler, “Castle OKs restrictions on adult entertainment,” News Journal, July 10, 1991, p.12

[10] Carolyn Lewis, “Sleepy Dagsboro gets wake-up call: Boom time predicted as sewer system nears completion,” News Journal, Tues Dec 24, 1991, A4.

On the Susex sewers saga – which involved the legislature overturning a Chancery Court decision within weeks of its announcement – see: Bruce Pringle, “Court Blocks Sewer Plants Outside District,” News Journal, Wed, Mar 21, 1990, p.1; Bruce Pringle, “Sussex: Change Sewer District Rules,” News Journal, Thu, Mar 22, 1990, p.1; Bruce Pringle, “Sussex OKs boundaries for sewer district,” News Journal, Fri, Mar 23, 1990, p.5 ; Nancy Kessler, “Castle Signs Sussex County Sewer District Bill,” News Journal, April 19, 1990, p.22; “Sussex County Has Eye On Parcel,” News Journal, May 30, 1990, p.2; Bruce Pringle, “Decision on Sussex disposal site expected within 2 weeks,” News Journal, Thu, June 28, 1990, p.1; Bruce Pringle, “Piney Neck Picked for sewage disposal site,” News Journal, Wed, July 4, 1990, p. 1

[11] Google translate latin for “With Sewers and Corporations, [the] City.”