Or, Shady Sovereignty at the Sands Motel

Corporate Voters Project – Research Note #7

Fenwick Island, as a modern community, was born a Delaware chartered corporation – which perhaps explains the municipality’s current attachment to corporate voting.

Today, the Town of Fenwick Island is (in)famous for being among the handful of Delaware municipalities that allows corporations to vote in local elections.[1] Like other towns that enfranchise fictional persons, Fenwick awards voting rights on the basis of residency and property ownership. The tiny beach settlement (year round pop. < 400) does put some limits on the corporate vote: since 2008, Fenwick’s charter has insisted on a “one-person/entity, one vote” principle, so property owners cannot double dip, voting as both individuals and as the entities they control; nor can they vote multiple times based on the number of parcels they (or the entity) own.[2]

Still, the political community that defines this narrow spit of land is firmly committed to oligarchy. Not only are non-resident property owners enfranchised, they can – and frequently do – make up a majority of the town council: only three of its seven members have to be full-time human residents.[3]

Recently, Fenwick was in the news for more than its generic lighthouse. In December 2025, the ACLU Delaware sued Fenwick in state court for violating the Delaware Constitution’s guarantee of “free and equal” elections conducted on the principle of “one person, one vote.” [4] The case is pending, though Fenwick Mayor Natalie Magdeburger told a reporter that it is “[o]ur belief is that everyone who pays taxes and is subject to our ordinances should have a vote” – including within “everyone,” the artificial entities commonly used to manage property. [5]

But how did this one-lane sea shore village become a rentiers’ redoubt? And when did it decide to shift from human rule to government for and by artificial entities? The legal history of this sandy spit on the Mason-Dixon line reveals the surprisingly recent roots of corporate voting, as an active practice – but also Delaware’s long tradition of privileging property over people.

~~~

Fenwick Island began its life as a distinct Delawarean community as an insider real estate speculation. In 1893, John H. Layton, Clerk of the Delaware House, bought out the owners of the barrier island that overlapped the Delaware-Maryland border, commonly known, if vaguely, as “Fenwick Island.”[6] Layton appears to have been the front man for a consortium of moneyed Delaware speculators, including legislators and industrialists, who quickly won two corporate charters to develop and manage the property.

The first, the Fenwick Island Company, was a real estate firm dedicated to managing “the business of purchasing, selling, holding, improving and managing real estate and island property.” The state granted it a $50,000 capitalization, extendable to $300,000, and the right to construct a railroad. (NB: unlike corporations under current Delaware law, the Fenwick Island Company’s founding document guaranteed shareholders’ democratic governance rights: all bylaws had to be decided by stockholders, and at all stockholder meetings, “all questions shall be decided by decided by a majority of votes case…each share of stock being entitled to one vote.” No question about rights to make proposals then, though later corporate advocates committing acts of law office history have offered alternate facts.)

The second was the Fenwick Island Gunning Club. Though Fenwick’s dunes and marshes were reportedly good territory for goose and duck shoots, its charter was silent on “gunning” (hunting) – but it did declare the corporation’s purpose as to provide for the “social intercourse and mutual improvement of its members.” (It’s founding members were the same as the real estate company.) [7]

Despite Layton’s string-pulling in Dover to acquire land and investment vehicles, not much came of the effort. Fenwick land sales didn’t boom, and neither a hunting resort nor a railroad was built. But in the decades following, Fenwick Island did become something of a cheap vacation spot, the site of regular evangelical camp-meetings, where vactioners enjoyed shore stays in rustic lean-tos and squat cottages [8]. After the state built a new road in the 1930s, cottagers petitioned for the right to purchase titles to the lots they leased – which they gained in 1942, after a legal battle over property rights between the state and the various “real estate men” resolved in the state’s favor.[9]

~~~

By 1953, the growth of Ocean City, Maryland next door, and the advent of better roads and more secure land titles, appears to have made Fenwick popular enough to lead property owners to petition the General Assembly for a charter, which duly passed into law without attracting comment. As with the corporation that preceded it, the town was to be run for and by property. Its government, a town council, was a body whose membership could only be composed of freeholders; those town councilors would be voted in by an electorate composed of “male or female” persons, twenty-one or over, who qualified for the franchise by being “freeholders,” either themselves or by marriage. Notably, while the original Fenwick Island town charter explicitly recognized that persons, partnerships, and corporations could be assessed taxes, implicitly it reserved voting rights for “persons” with qualities of gender and age – that is, human beings. [10]

Unusually for Delaware municipalities, the Town of Fenwick Island has never revised its charter wholesale, but only amended it – making it more difficult to track when corporate voting arose. The first evidence of the practice in state law appears in 1965, when the town charter was amended to allow the authorities to issue infastructure bonds. As with other municipalities, this new capacity for extending municipal credit came with new oversight: special hearings to propose and discuss the borrowing, and a special election to obtain voters’ approval. These special bond elections expanded the electorate to corporations, explicitly, and tilted power toward wealth: “every owner of property, whether individual, partnership or corporation” could vote, and they “shall have one vote for every dollar” paid in tax. Voting could be in person “or by proxy.” In other words: a few months before the US Congress would pass the Voting Rights Act to ensure all Americans could participate in elections equally, the Town of Fenwick Island in still-segregated Delaware extended new voting rights only to propertied fictional persons. [11]

Universal human suffrage did not reach Fenwick Island until after man had visited the moon and disco conquered the dance floor. In 1979, a charter amendment lowered the voting age to eighteen, and specified that all humans residents in town on election day were “entitled to vote.”[12]

This new regime was not without its complications, however. In 1981, Fenwick’s police chief, James L. Cartwright, was disqualified as a candidate for a town council race because he did not own a sufficiently decisive property interest. A non-resident, Cartwright had thought himself qualified, because he owned a minority stake in a corporation that owned real estate in town: 20/400 shares in the Sussex Sands Inc., a corporation that owned and operated the Sands Motel. Citing an unpublished “municipal policy” that granted only majority stockholders of property-owning corporations the right to run for office, the town council rejected Cartwright’s bid for candidacy – and he found a lawyer to contest the rejection. His attorney, Robert C. Wolhar, discovered that “at least three of the current councilmen” in Fenwick were similarly deficient – owning only a minority share of the same motel corporation. A town council thusly improperly constituted, Wolhar alleged, could not govern legally, and thus “all the ordinances and police arrests made in the small seaside town may be illegal because some of the commissioners … were seated illegally.” [13]

The Delaware Department of Justice, following its characteristic approach to white collar law enforcement, declined to pursue the matter. The next Fenwick election – with a high turnout of 400 – swept in a slate of fully qualified candidates, seemingly resolving the immediate issue.[14] Following this dispute, Fenwick amended it’s charter several times in the early 1980s, using increasingly convoluted language to define qualifications for voters and candidates for office. In 1986, it settled on the exclusion of “freeholders” who “who claim title to real property by virtue of their ownership rights in a limited partnership, a corporation, or other fictitious name association, or in special circumstances, where an organization is formed for the apparent or express purpose of taking title to property principally to acquire the right to vote, or a person or persons who claim title to less than 50 percent of the real property which is owned jointly with a corporation, limited partnership, or fictitious name organization.”[15] How the town council was to discern the “apparent or express” purpose of a corporation was not specified.

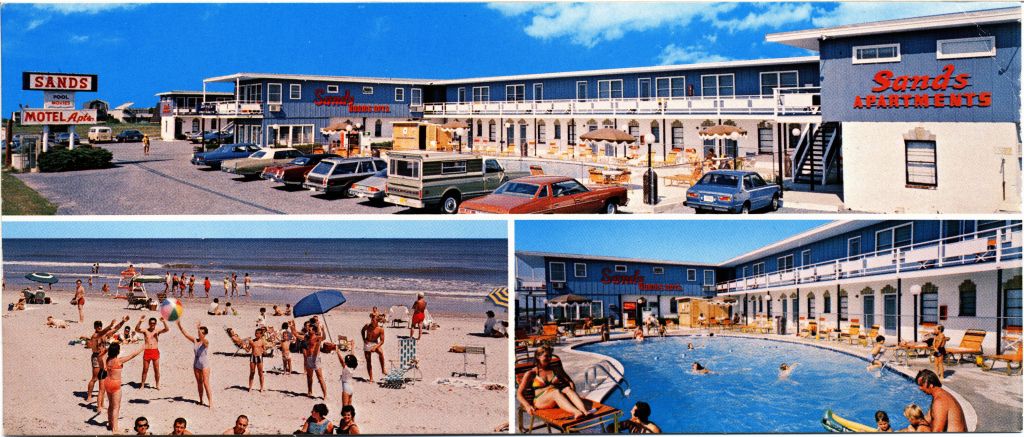

Sidebar: Sussex Sands, Inc., the corporation that owned the Sands Motel and in which Cartwright and several town councilmen owned minority shares, remains a going concern. John Caldwell, the owner and operator of the motel (and failed town council candidate himself) died in 1982, but his widow remains listed as the registered agent for the corporation, at the motel's original address (a comparison of a 2012 Google Street View image and a 1979 postcard featuring the motel reveal the property to be the same). In 2020 the motel was remodeled and renamed, and is now branded as an upscale Hilton property, “Fenwick Shores.”[16]

The latest major change with regard to corporate voting in Fenwick Island was made by amendment in 2008. In a sweeping revision of the charter’s voter qualification section, the amendment inserted a by-then increasingly common (in Delaware) “one-person/entity, one vote,” provision, limiting both natural persons and artificial entities to one vote, total, no matter how many parcels of property they owned. It also specified more clearly the documentation needed for corporations (a notarized power of attorney designating a proxy voter; corporations still need humans to take action).

In keeping with twenty-first century Delawarean practice, the provision of corporate voting went unremarked in public discussions of the amendment process. The town manager, Anthony Carson, justified the revision only in terms of needing to increase the town’s “outdated” credit limit, raise funds sufficient to build a new “public safety building.” At least in news reports, the “one person/entity” rule – or corporate voting, more generally – did not warrant a mention. [17] A 2018 charter amendment increased the burden on human voters – requiring more identification to establish residency – but left procedures for corporate voters unchanged. [18]

~~~

Human democracy – government for the people, by the people – has never taken firm root in the sandy soils of Fenwick Island. A land imagined speculatively from its first legal organization, property has always called the shots there. Controversy over governing power, when it has occurred, has been over how much control a given person (natural or legally fictitious) has over real estate title – not whether people matter more than property.

Fenwick Island, then, mirrors in some ways Delaware’s increasingly unambiguous preference for corporate controllers over community stakeholders. Whether it’s taxes at the beach, or plaintiffs at the bar, the state’s governing institutions seem to incline to consolidated power over any other available option. It remains to be seen how this system will weather the strong storms we know are coming.

—–

Header Image Source: Sands Beach Resort Motel, 1979, Postcard, 21 x 9 cm, Special Collections, University of Delaware Library, GRA 0138, Delaware Postcard Collection, https://digitalcollections.udel.edu/Documents/Detail/sands-beach-resort-motel/164590.

[1] Corporations and other artificial entities, including “partnerships, trusts, and limited liability companies” – provided they are domiciled in the state, and own property in the town. Charter of Fenwick Island, Sec. 9(A)(2), State of Delaware, accessed January 20, 2026, https://charters.delaware.gov/fenwickisland.shtml

[2] 76 Del. Laws, c. 363 (2008)

[3] Charter of Fenwick Island, Sec. 6 and Sec. 9, State of Delaware, accessed January 20, 2026, https://charters.delaware.gov/fenwickisland.shtml

[4] ACLU-DE Files Lawsuit Against Fenwick Island for Allowing Corporations to Vote in Local Elections, (ACLU Delaware), December 3, 2025, https://www.aclu-de.org/press-releases/fenwick-corporate-voting/ ; Jacob Owens, “ACLU Sues Fenwick Island over Non-Resident Voting,” Spotlight Delaware, December 5, 2025, https://spotlightdelaware.org/2025/12/05/aclu-sues-fenwick-island-over-non-resident-voting/. (NB that the Spotlight article significantly misstates the core contention of the ACLU’s suit: the organization is contesting Fenwick’s practice of non-human voting – not non-resident voting).

[5] Kerin Magill, “Fenwick Island Responds to ACLU Lawsuit,” Coastal Point, December 12, 2025, https://www.coastalpoint.com/news/communities/fenwickisland/fenwick-island-responds-to-aclu-lawsuit/article_0ff740be-481b-43c5-8271-6c2faaae1899.html.

[6] The newspaper reporting on Layton’s purchase is somewhat contradictory, but it appears he gained title to the island by buying out two members of the Gum family, Dr. F. M. Gum and William A. Gum, for a total of $6,750, in separate transactions. Layton’s purchase was covered in an amused tone by otherwise bored legislative reporters, who noted his enthusiasm for the property and its possibilities for duck hunting and sheep herding . “Bought Fenwick Island,” Morning News, April 10, 1893, p. 4; “Legislative notes,”Every Evening, April 18, 1893, p.1; “They Own the Whole Island,” Evening Journal, April 28, 1893, p.5; “Clerk Layton’s Purchase,” Every Evening, April 28, 1893, p.1.

There were earlier Delaware corporations with “Fenwick Island” in their names, but these appear to have been aimed at improving water infrastructure – ditch digging. See 14 Del. Laws, c. 149 (1871), “An Act to Incorporate the Fenwick’s Island Improvement Company,” March 15, 1871, pp. 217-220; 18 Del. Laws, c. 375 (1887), “An Act to Incorporate the Fenwick’s Island Beach Company,” April 14, 1887.

[7] “A Fenwick’s Island Boom,” Every Evening, April 19, 1893, p.2;

19 Del. Laws, c. 982 (1893), “An Act to incorporate the Fenwick Island Gunning Club,” April 24, 1893; 19 Del. Laws, c. 722 (1893), “An Act to incorporate the Fenwick Island Company,” April 25, 1893 pp. 972- 975. (On shareholder rights, see 19 Del. Laws, c. 722 (1893), p. 973-74.)

[8] “Fenwick Island Camp,”Every Evening, April 25, 1921, p.6; “State Offers Vactionists Rest,”Newark Post, July 26, 1922,p.2 ; “Delaware Vacation Spots Attract Pleasure Seekers,”Morning News, Feb. 27, 1937, p.27

[9] “Ask Right to Buy Land,”Morning News, June 16, 1938, p.20; “Fenwick Island Land Sale Ready,” Morning News, January 5, 1942, p.18; “Delaware to Sell Fenwick Island Land: Owners of Cottages Get Right to Buy Lots on Ocean Front,”Daily Times (Salisbury, MD), Jan. 5, 1942, p.8

[10] “Other New Bills,” The Morning News, March 27, 1953, p.10; “Other Bills Passed,” Morning News, July 2, 1953, 40; 49 Del. Laws, c. 302 (1953), “An Act to Incorporate the Town of Fenwick Island, Delaware,” July 8, 1953, pp. 602-23 (on voter qualifications, see p.606, on taxes, p. 612).

In 1962, a Washington DC paper reporting on Fenwick’s amenities for vacationers – including a beach that coughed up silver dollars – noted that “the council is elected by everyone registered on the property tax rolls.” See: Janet Koltun, “Money Banks Deposits Dwindle but Fun Rises,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), Aug. 5, 1962, C-6

[11] 55 Del. Laws, c. 89 (1965), “An Act to Amend Chapter 302 … ‘ An Act to Incorporate the Town of Fenwick Island, Delaware’ By Authorizing the Borrowing of Money and Issuing Bonds Therefore…,” (May 27, 1965), pp. 360-62.

[12] 62 Del. Laws, c. 3 (1979), “An act to amend chapter 302…,” February 6, 1979, p.4

[13] Ed Shur, “Arrests May Be Illegal,”Daily Times (Salisbury, MD), July 14, 1981; Grayson Smith, “Fenwick Election Imperiled,”Morning News, July 14, 1981, p. C2

[14] “Two Candidates run into flap in Fenwick election,”Morning News, July 31, 1981, p.C4; “Election Settles Issue in Fenwick,”Morning News, Aug 2, 1981, p.B2

[15] 65 Del. Laws, c. 321 (1986), p. 603. Prior amendments include: 64 Del. Laws, c. 53 (1983). p. 110 and 63 Del. Laws, c. 371 (1982), p.775.

[16] Sussex Sands, Inc., file no. 858088, Entity Search Database, Delaware Division of Corporations, https://icis.corp.delaware.gov/Ecorp/EntitySearch/NameSearch.aspx; Sands Beach Resort Motel, 1979, Postcard, 21 x 9 cm, Special Collections, University of Delaware Library, GRA 0138, Delaware Postcard Collection; “J.R. Caldwell, Sands Motel owner, dies,” Morning News, Feb. 2, 1982, C4;

[17] 76 Del. Laws, c. 363 (2008) ; Andrew Ostroski, “Fenwick Island Officials Meet to Change Charter,”Daily Times, July 25, 2008, B4.