Or, Delaware Stands Ready To Perpetrate Any Sort of Corporate Enormity (Again)

Mark Twain never said that “history never repeats itself, but it rhymes.”(1) But if he had taken time out to consider the past, present, and future of corporate corruption, with particular attention to the the diminution of shareholder rights, I put it to you, dear reader – he might’ve done.*

The author of the Gilded Age came to mind recently when I ran across more evidence that our simulation is caught in a loop, repeating the obvious mistakes of the past, again. William Z. Ripley (believe it or not) was who caught my attention.

In the mid-1920s, Ripley, an Ivy League social scientist and popular Progressive railroad reformer, took aim at corporate governance; or rather, the startling lack thereof. In a series of Atlantic articles and then in a 1927 book, Ripley catalogued the recent legal and financial innovations that had put “Main Street” at the mercy of “Wall Street” in new and destructive ways.(2) Though he claimed to not be any kind of muckraker (or, horrors, a socialist), Ripley still wanted to get down to the “root of things” – to diagnose how “property” and been “allowed to degenerate into an instrument of oppression” in America.(3)

Delaware, in part, was to blame. (But you knew that already.)

For Ripley, private property turned into a tool of tyranny when corporations severed ownership from control. Ripley argued that this wicked wound had first been cut by the proliferation of corporations across all lines of business – a tendency, he noted, that was peculiarly well advanced in the US, but not in Europe. That laceration was deepened by the widespread practice of watering-down corporate shareholder rights. He was particularly disturbed by two phenomena: the advent of “no-par” stock issuances, and the rise of non-voting tiers of stock.

Of the two, no-par stock bothered him more. Prior to its invention, corporations assigned each unit of stock a face-value, and printed that value (say $50) on the certificate; that amount was “par.” The buyer and holder would then know they had contributed $50 to the capital of the Kennebec Ice and Coal Company, Inc. – say – and that that amount was their claim on a particular percentage of the firm’s equity; secondary traders would also have a clear sense of how the current price of the stock compared to its initial value. If a corporation later decided to accumulate more capital by selling additional equity, common law practice before the late nineteenth century made it unlawful to offer new shares at less than the original par value – and existing shareholders had a preferred right to buy in to the new issuance, and thus keep the size of their stake equal with other shareholders.

The advent of no-par stock changed all that. In practice, no-par stock issuances meant “much below par” and sometimes “zero cost.” And for Ripley, they destroyed the moral relationship between investors and the corporation. He decried them as an “egregious malversation of the rights of shareholders and of the public generally” because they allowed companies to dilute stock, effectively robbing earlier investors of value and future buyers of much-needed information. They could also inflate the control of well-positioned insiders, like members of the board of directors, who could load up on new no-par shares to acquire more dominant voting rights.(4)

For similar reasons, Ripley opposed the proliferation of corporations issuing non-voting stock. Rooted in the deep Anglo-American legal tradition, he considered corporations to be voluntary commonwealths, premised, like all republican polities, on equality among members to function (municipalities are also a form of corporation, one might here recall…). Tiered stock structures separated equity into classes with different voting rights – building in inequality. A corporation might issue 100,000 shares, divided between 1,000 Class A shares, with rights to vote for the board of directors, and the remaining 99,000 as non-voting Class B shares – securities with no controlling powers, just vague claims to a portion (“aliquot”) of the corporation’s wealth.

Ripley thought both methods were perversions of the “essence of corporate democracy” – the premise that “all members of the company shall stand upon an even footing with one another.”(5) This posed a problem for corporate investors, internally – an inside group had means to gain control without matching their stake, and therefore the means to steal from other stockholders, by arranging sweetheart contracts for themselves, or simply by voting special dividends. It also posed a dilemma for society, at large, because in combination with holding companies and trusts, it accelerated the dispersal of responsibility for corporate actions beyond any readily identifiable individuals – common stock holders didn’t have any say on corporate decisions! –while, paradoxically, concentrating control of corporate wealth into an ever-smaller number of hands (again via holding companies). In a moment where corporations had become not just one form of economic entity among many, but the default choice for *any* and *every* form of business, Ripley saw an invitation for un-remediable theft and fraud – and documented dozens and dozens of actual instances of it.

And wouldn’t you know it, Delaware shows up as one of the authors of this disaster! Ripley traces the spread of these terrible innovations to competition between states for “chartermongering.” The race-to-the-bottom between sovereign states for charter revenue opened the door for ever-looser laws, making insider dealing between directors and controlling stockholders not only legal, but a core business strategy for modern corporations. “The little state of Delaware has always been forward in this chartermongering business,” he noted – and led in this laxity, too. (Though unlike many later Delaware lawyers and state officials, Ripley in 1927 doesn’t credit Delaware with dominating the chartermongering business; the First State is one of several mean jurisdictions, like Maine, Arizona, and New Jersey, making life worse for all Americans).(6)

Ripley is worth quoting at length about how this corrupt legislative process proceeds, partly because he really decides to go for the gusto in his language:

“But it is the evidence of an unholy alliance between private profit and the exercise of this supposedly sovereign function which is at times the most debasing in its influence. The system tends to create a horde of shysters, ready to perpetrate any sort of corporate enormity, provided only that the fees are sufficiently ample. And attorneys, on their part, as one of them writes me, ‘pick their states of incorporation as you or I would pick out a department store at which to trade.’

Another shameful angle to this business is that it tends to envelop our state legislative chambers in a noisome atmosphere of political honeyfugling, if not of downright corruption. A minor modification of a state statute may be worth large sums of money, because of its effect either upon plans in contemplation, or else as affording possible relief from the untoward results of acts already committed. And just because these amendments are seemingly so insignificant, they may be slipped through without arousing comment and perhaps almost entirely without notice. The temptation to spend money in what amounts to bribery, in order to attain such results, may upon occasion be very great. Nor need the immediate accountability for such corruption necessarily rest upon the corporations themselves. The system gives rise to a considerable body of irresponsible intermediaries — henchmen, lobbyists if you please — specialists in such branches of the law, hangers on about the state capital. The great corporation merely whispers its need. Subservient agents hasten to bring about the desired result, and perhaps no questions are asked. …”(7)

Now, if “political honeyfugling, if not downright corruption” doesn’t describe the ugly process of passing SB 21 (and its recent predecessor “reforms”), I don’t know what does.

But beyond the remarkable resemblance between Ripley’s description of how legislative corruption works at the state level – the “henchmen” and other “subservient agents” who rush a bill through are extremely familiar figures in Delaware – the substance of Ripley’s complaints about the evils of insider string-pulling toll quite recognizable tones. He’s lamenting the structural abuse of what today’s corporate legal specialists call “private ordering.” And easing the rules on private ordering for controllers is what current Delaware legislators, and their affiliated henchmen, have been gunning for, over these last few years.

There’s another thread that links Ripley’s century-old critique to today’s miseries. Ripley was an acknowledged influence on Adolf Berle and Gardiner Means, his contemporaries and the major (if constantly misread) theorists of structural problems in corporate governance. Like Berle and Means, Ripley’s concern was about the problem of control in corporations – not the divide between professional managers and stockholders owners, per se, as is usually claimed, but the one between any stakeholders in the control of the business itself.(8) Ripley, like his colleagues Berle and Means, cared about any mechanism that produced a power imbalance between members of a corporation – and in the 1920s, as now, that threat came most clearly from controlling minority shareholders, not the managers they hired.

Berle and Means are now the more famous writers – but a century ago, Ripley was a much louder and more well-known voice.(9) Over the next decade his profile only grew in prominence, because, among other things, he predicted the Great Depression (which … other famous economists quite infamously did not). Ripley’s concerns with corporate opacity, controlling shareholders, and insider dealing contributed directly to the New Deal reforms that came less than a decade later, after the crash (and specifically the federal Securities Exchange Act of 1934). It’s not a stretch to say that the Ripley’s specific complaints shaped the specifics of financial regulation in the United States, at least until recently.

Which leads me back to my sense of chronological vertigo. In the last few years, the Delaware General Assembly has taken a hacksaw to shareholder rights, reversing judicial rulings that had curtailed the amount of insider dealing (“private ordering”) that corporate boards could do. Alongside this strangling of the main venue for private redress of corporate wrongs, federal regulatory agencies, most notably the SEC and CFPB (but increasingly the Federal Reserve, too), have been captured or closed outright – eliminating the public arm of corporate regulation. The nation’s feeble protections against the same corporate fraud and thefts Ripley decried are now dead letters in their state and federal forms – and controlling shareholders are free, once again, from any restraints that bound them from freely picking the pockets of fellow shareholders, and citizens.

Thus, the unbound and unaccountable corporate immorality that Ripley decried in his own time – the oppressive property of corporate property – is back again, a boot pressing on all of our necks. Which makes it all a bit rich – or perhaps a bit ironic? – that the group of Delaware legal professionals, academics, jurists, and defense attorneys, who are – putatively – among most familiar with Berle and Means (and, thus Ripley, one step removed) should have been the intellectual architects of this repeat disaster.(10)

One can only hope that long dead Progressives like Ripley retain the capacity to haunt their traitorous professional descendants, even as the rest of us are horrified by the specter of what Delaware has, once again, wrought.

——

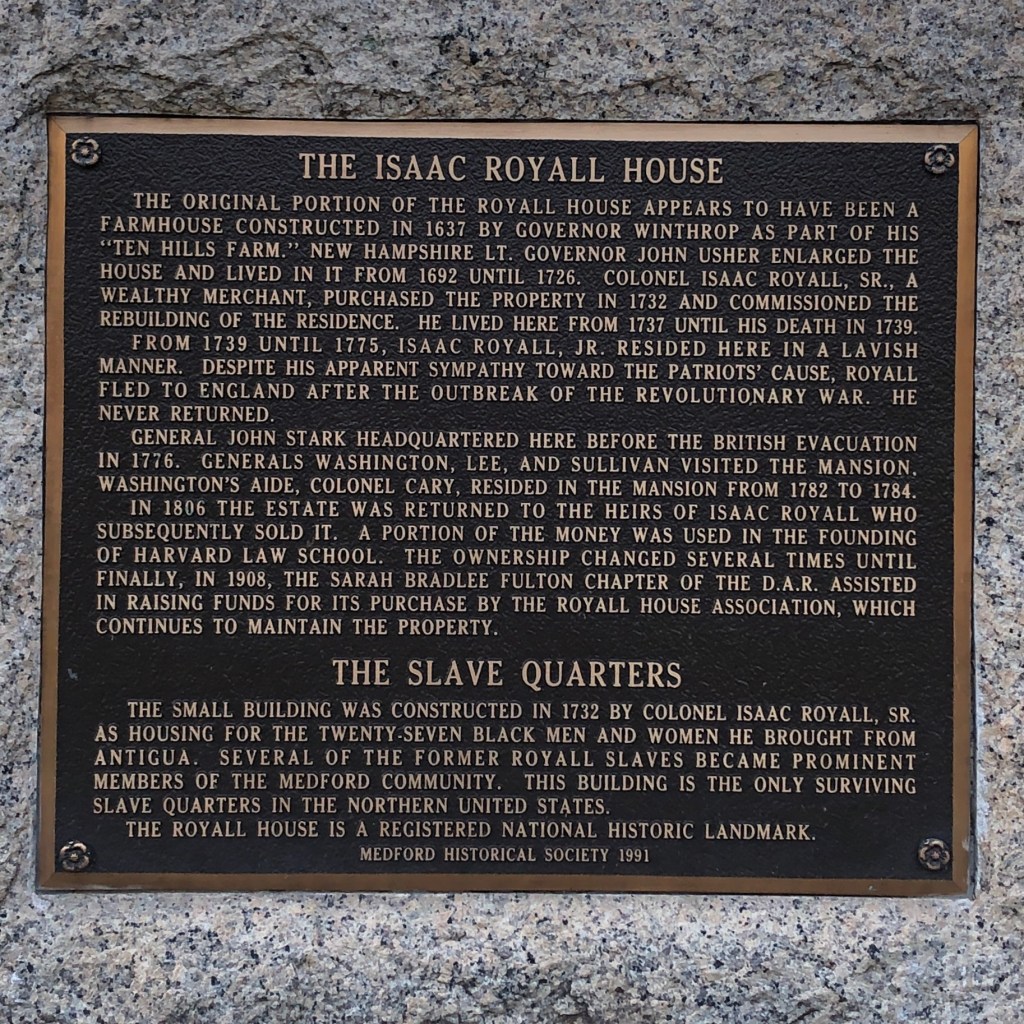

A brief note: This is not a William Zebina Ripley fan account. He was one of the most influential writers on modern scientific racism. He came to national prominence first, not for his scholarship on colonial finance, railroad management, or corporate governance, but for his 1899 book, The Races of Europe. Originally developed as a lecture series at Columbia University and at the Lowell Institute, it’s a fantastically stupid piece of work, exemplary of the time, filled with tedious ethnic and racial stereotypes “proven” by tendentious skull measurements. It was, of course, a huge hit with eugenicists, white supremacists, and other evil, awful people, both in the US and abroad – including Madison “Hitler’s My No. 1 Fan” Grant. Ripley’s intellectual legacy has a body count in the hundreds of millions – and one that grows by the day, as his theories persist through the AI-“trained” ideas drug-addled billionaires and quack failsons have used to justify horrific revisions in US federal policy. He’s also from Medford, MA (derogatory).

——

*You’re going to tell me the guy that wrote A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court couldn’t time travel?

1. As far as I know, Twain never used the phrase, exactly – though in his 1873 co-written novel, The Gilded Age, a character quotes a newspaper offering a similar sentiment:

“History never repeats itself, but the Kaleidoscopic combinations of the pictured present often seem to be constructed out of the broken fragments of antique legends.”

~Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner, The Gilded Age: A Tale of to-Day (American Publishing Company, 1873), p.430.

Quote Investigator finds the closest instance of this phrasing in a poem by John Robert Colombo – in the text, the phrase is attributed to Twain. John Robert Colombo, “A Said Poem,”Neo Poems, p. 46.

2. William Z. Ripley, “From Main Street to Wall Street,”The Atlantic, January 1, 1926; William Z. Ripley, “The Shareholder’s Right to Adequate Information,”The Atlantic, September 1, 1926; and William Z. Ripley, Main Street and Wall Street (Little, Brown, and Company, 1927)

3. “Personal Note,” in William Z. Ripley, Main Street and Wall Street (Little, Brown, and Company, 1927), v.

4. Ripley, Main Street and Wall Street, 46.

5. Ripley, Main Street and Wall Street, 38.

6. Ripley, Main Street and Wall Street, 30.

7. Ripley, Main Street and Wall Street, 35-36

8. As historians Ken Lipartito and Yumiko Morrii note, “[t]he conflict that Berle and Means emphasized was not between managers and owners, but between owners and owners.”Kenneth Lipartito and Yumiko Morii, “Rethinking the Separation of Ownership from Management in American History,”University of Seattle Law Review 33, no. 4 (2010):1048; on Berle and Means’ relationship to Ripley, see p. 1045-46 (though note that Lipartito and Morrii misdate the publication of Ripley’s “exposé” in the text to 1928; it was 1927).

9. He got a lot of positive press, and was recognized as sufficiently prominent to scare the NYSE in to pretending to act to prevent no-par stock issuances. Ralph W. Barnes, “A Professor Who Jarred Wall Street,”Brooklyn Eagle (New York), April 18, 1926; S. T. Williamson, “William Z. Ripley –and Some Others,”The New York Times, December 29, 1929. (He also made the news wires when he was injured in a car accident in Manhattan, riding with a woman who wasn’t his wife. See, for ex: “Prof. Ripley in N.Y. Taxi Crash,”Transcript-Telegram (Holyoke, Massachusetts), January 20, 1927; “Noted Economist Hurt in Crash,”The Herald Statesman (Yonkers, NY), January 20, 1927.

10. For examples of the legal beagles undoing Ripley’s work, and the New Deal era’s financial protection, session by session, see: William Chandler and Lawrence Hamermesh, “Delaware Plays Fair: Corporate Law Amendments Will Protect Investors,”The News Journal, March 5, 2025; William Chandler and Lawrence Hamermesh, “Delaware’s Corporate Law, Proposed Amendments Play Fair,”Delaware Business Times, March 6, 2025; Lawrence Hamermesh, “Letter in Support of the Proposed Amendments to § 122 DGCL,”The Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance, June 11, 2024; Lawrence A. Hamermesh et al., “Optimizing the World’s Leading Corporate Law: A Twenty-Year Retrospective and Look Ahead,”Business Lawyer 77, no. 2 (2021): 321–80.

Cf. Joel Friedlander, “Are Hamermesh, Chandler and Strine Making Delaware Corporate Law Great Again?,”The News Journal, March 17, 2025.