Or, Found Historiography

What should I read to learn more about history?

That’s a question that all historians wrestle with — certainly one that I revisit anew every time I find I need to orient myself when the research trail leads to unfamiliar temporal territory. It’s also one that successful hacker-entrepreneur Paul Graham has pondered; it appears in the middle of his personal website. Graham’s answer, while intended to guide the enthusiastic amateur, hits quite close to how the pros do it:

The way to do it is piecemeal. You could just sit down and try reading Roberts’s History of the World cover to cover, but you’d probably lose interest. I think it’s a better plan to read books about specific topics, even if you don’t understand everything the first time through.

And that, ladies and gentlemen, is basically how History Grad School Works, iteration one. For the full training regimen, the one that all the folks with extra letters after their names have done, you just rinse and repeat, staying in the same topical territory, until what was once unfamiliar now seems like family, complete with creepy uncle and dotty aunts.

I bring up Graham’s answer, not just because it gives away guild secrets for free, but because it suggests that the worlds of hacking and history are closer than they might appear. Now, as I may have mentioned before, my interest in this kind of comparison is long-standing, and possibly the result of unhealthy reading habits; but I think other areas of Graham’s writing lend credence to this idea if we consider both fields as realms of practice (and lest you think that Graham is an outlier as a hacker, note that the guy publishes with O’Reilly).

Look, for example, Graham’s advice on generating ideas for startups:

It would be closer to the truth to say the main value of your initial idea is that, in the process of discovering it’s broken, you’ll come up with your real idea.

The initial idea is just a starting point– not a blueprint, but a question.

Again, this comes remarkably close to how a historian — and perhaps any scholar — works. In fact, the whole apparatus of scholarly production, for all its faults, is set up to follow this procedure, albeit in a more formal way: ideas go from seminar papers to conference presentations to journal articles to books to reviews and back into seminars, sloughing off old accumulations through further refinement of questions.

So what I think Graham’s advice reveals is a similarity in approach, which I, along with C. Wright Mills, would characterize as craftsmanship. ‘Doing history’ is like ‘doing programming’ — an intellectual affair, one with few “material” results perhaps, but one that only becomes realized through iterative production, through a working and shaping of material, often collaboratively. It isn’t a science, it isn’t quite an art, but has aspects of both, and is deeply intertwined with a particular philosophical approach to work. It’s not quite Zen and the Art of Bibliographic Maintenance, but not too far off, either.

I think Graham’s (and Mills’s and Pirsig’s) thinking on how this work gets done represents a strong challenge to both C.P. Snow’s much-celebrated concept of “Two Cultures”, which represents the humanities and science as having had a major failure to communicate, as well as Matthew Crawford’s argument against white-collar work, especially scholarly — he was formerly a philosopher — as necessarily alienating.

If intellectual work is a craft (for meanings of “craft” that are continuous across fields) I think then we should rethink how bright the line separating each of these dualities — manual vs. intellectual, science vs. humanist, etc — really is. And at the very least, I think working as if one’s work is a “craft” is a far more productive way to approach labor, on both ends of the spectrum, not least because it makes incorporating new insights easier.

Of course, I may be drawing far too much out of Graham’s essays. It may be that programming, hacking, and computer science in general, is unique it how closely the mind set mirrors the methodology of the lesser humanist disciplines. Or perhaps that the mythos of hacker culture — however the work may actually be in real life — draws strongly from the mythos of university life, and that provides the (fictional) bridge.

Or maybe any sufficiently advanced technological pursuit is indistinguishable from history.

*Not to be confused with History Hacker — Bre Pettis’s show does look pretty awesome, though it doesn’t appear to have made it past the pilot stage.

1. Okay, “middle” is a bit strong. It’s in his RAQ (“Rarely Asked Questions”) file. But still! And a h/t to Marginal Revolution for pointing me to Graham’s website.

2. Partly as a result of a youth spent immersed in William Gibson et al., programmers are the folks I think of when I hear “knowledge worker” or “symbolic analyst”– not Richard Florida’s “creative class” of boho architects, nor the conspiracy-busting whiz-geezer of Dan Brown novel fame, nor the caricatured Foucauldians that nostalgic neoconservatives have in mind when pining tenderly for a time when untrammeled free markets and long hours of manual labor saved Real Men from self-alienation.

3. Mainly through hand-wringing and head waggling.

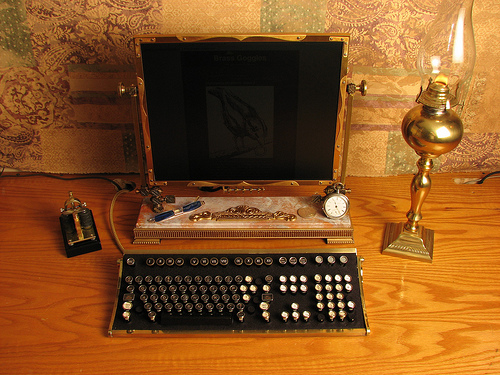

Image cite: bdu, “eniac,” Flickr, CC License